Putting Nation Before Party

Andrew Barber — September 27, 2023

In 2023, the deep rift in Washington between Republican and Democratic leaders makes it difficult to imagine that effective bipartisan cooperation is even possible.

This has not always been the case.

C. Douglas Dillon, a Republican, was an investment banker who served as a diplomat and Undersecretary of the State Department under President Eisenhower but later became the Secretary of Treasury under Presidents Kennedy and Johnson.

A canny political operator, Dillon successfully navigated partisan conflict in the 1950s and 60s to spearhead tax and tariff legislation, formulate a strong dollar policy, and develop a working relationship between the Treasury Department and Federal Reserve that has since served as a template.

Dillon’s remarkable career is the subject of a new book, “The Dillon Era: Douglas Dillon in the Eisenhower Kennedy and Johnson administrations,” written by Richard Aldous.

Aldous is the Eugene Meyer Professor of British history and culture at Bard College. He received his Ph.D. from Cambridge and has authored and edited 11 books.

Gravity Exists spoke with him about Dillon and his legacy.

Listen to the interview:

Gravity Exists –Professor Aldous, thank you so much for joining us.

Richard Aldous – Thanks so much for having me. Andrew.

GE – Douglas Dillon was a Republican who successfully worked in the cabinets of both GOP and Democratic presidential administrations. I’m certain that when you talk to people, it is something that they remark on because it seems incredible to us today in 2023, given the extreme partisan divide in US politics.

RA – You’re absolutely right that it is very striking that here is this man who was an important figure in the Eisenhower Republican administration in the 1950s. He was an ambassador in Paris and then number two in the State Department. He was actually the favorite to be the new Secretary of State in the Nixon administration if Nixon had won the 1960 election.

But then it turns out that he is invited by John F. Kennedy to become Treasury Secretary. And he accepts that position — along with other Republicans like Robert McNamara, for example, and George Bundy, who became a National Security Advisor. And so, these other prominent Republicans join that Democratic administration in a way that seems quite striking to us today.

The Trump administration didn’t have any Democrats in the cabinet. Michael Flynn was a short-lived Democrat as National Security Advisor. The current Biden administration has no Republicans in the cabinet. So, it speaks to a very, very different time.

We should, however, be careful not to romanticize it too much that Eisenhower and Nixon were both furious with Dillon for accepting the position, even though ultimately, they both recognized that you had to put the national interest above party interest.

GE – Dillon was born into Wall Street aristocracy. He served as the chairman of the investment bank that was named after his father. Did this career as a financier particularly well prepare him for politics?

RA – In many ways, when he came into politics, he was a complete neophyte. He hadn’t really any political experience. So, he did have to draw on that experience of Wall Street.

As you say, his father, Clarence Dillon, the head of the famous investment firm Dillon Read, was also one of the richest men in America. So, Douglas Dillon came from this very wealthy family and had this experience on Wall Street that gave him a kind of technical ability and also a certain calmness in the way that he dealt with things. I guess if you’re used to dealing with the amounts of money — the kind of deals that he was putting together in the 30s and 40s, then you have to have a certain perspective and calmness in the way that you do things.

He also had, behind that calmness, a kind of ruthlessness, a killer instinct politically.

That calmness and the great courtesy that he had on a personal level often disguised that much more ruthless side. So, first as ambassador, and then in the State Department, and then in the Treasury, he was able to use all of these skills. The technical ability, the great courtesy, the comfort that comes from dealing with people. But also, hidden beneath it, that killer instinct which, as somebody who has never worked on Wall Street, I nevertheless imagine that you have to have working in that environment.

GE – A commonality that stands out between the leaders profiled in your book — JFK, Richard Nixon, obviously President Eisenhower — was that they had all lived through World War Two. From your perspective, did that experience, where personal rivalries had to be put aside for the pursuit of the common good, contribute to a more collaborative approach that may have fostered bipartisan cooperation?

RA – I think that’s right — this idea of the greatest generation.

Clearly, there is something about that shared experience that these characters had to go through. As a very young man, Dillon certainly went through it when he worked for James Forrestal in Washington, which was an old Dillon Reed connection. Then, when he served his time in the Navy, he flew very often on naval reconnaissance missions and so on. In an interview, he said, “Yes, I saw tracer fire,” which is that very understated way that these characters often spoke about their wartime experience.

That’s something he shared with JFK and with Nixon, and I think you’re right that it does maybe create this more collaborative experience. It’s one of the strange things that we often forget that Nixon and JFK in the 1950s were quite close. There are wonderful stories about them sharing train rides and so on together; JFK helping Nixon financially; and so on.

I think that all these characters, from that experience, drew a kind of a sense of what the American interest was. We come back to that, again, that is not just about policy. They recognize that, to some degree, politics is a game that is played. But behind the scenes, these ties that bind are very important.

GE – As a banker by profession, Dillon was tapped by JFK to head up the Treasury Department. He had served in the State Department before that under Eisenhower, however. This was all going on during the height of the Cold War. As he approached some of the key initiatives during his period as Secretary of the Treasury — defending the dollar, liberalizing tariffs — do you think he viewed economic policy as a tool to further the foreign policy goals of the US?

RA – Yes, very clearly. It was the reason that John Foster Dulles, who was the Secretary of State under Eisenhower, brought him into the State Department to do economic foreign policy.

This was a new way of thinking about foreign policy. That you had to look at the emerging countries, countries in places like Latin America, and the economics, for example, loan deals, development. These kinds of things were essential to the way in which the United States prosecuted the Cold War.

He was involved in putting together loan deals, development, banks, and so on, for those kinds of purposes. That’s an agenda that he carried on when he moved to the State Department. One of the most important things that he did was the Punta del Este conference, where he put together this massive development deal for Latin America. Hugely influential and important.

So yeah, this kind of technical skill that he had. This ability to put together deals, drawing on that Wall Street experience, was very important.

I think another thing which was hugely important for him was the balance of payments deficit and the gold crisis. Gold was pegged at $35 an ounce, and this was incredibly difficult for the United States because countries weren’t simply able to draw on gold reserves without draining gold from American coffers. That, coupled with the balance of payment deficit, meant that it was a huge problem for the administration to deal with.

Kennedy said that there were two things that kept him up at night. One was nuclear holocaust and the idea of a nuclear war. But the second one was the balance of payment crisis. So, this was something that put Dillon right at the heart of the administration.

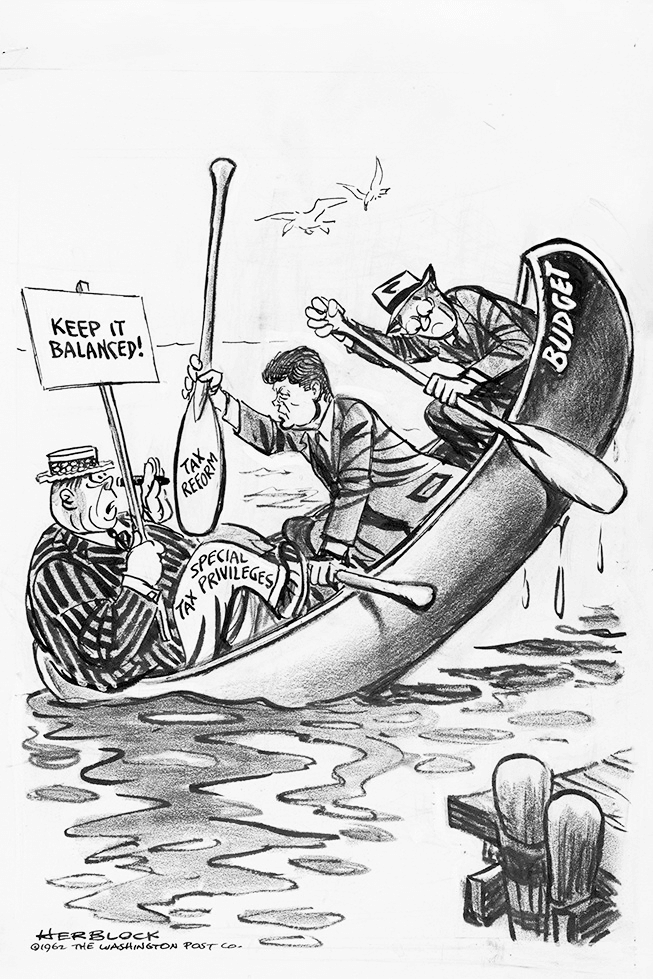

GE – In another major contrast with the present day, Dillon, who, again, was a Republican, proposed tax policies that were meant to advance the economic goals of the JFK administration. The modern Republican Party is primarily focused on dismantling the IRS, while critics of the current Democratic Party leadership argue that they’re primarily focused on social engineering. So, a Republican Treasury Secretary in a Democratic administration advocating a pragmatic centrist tax policy would seem completely implausible today.

RA – It was very politically controversial, even in the 1960s. The Revenue Act of 1964 brought the marginal tax rate down from 91 percent to 70 percent. This was a big, big deal in terms of politics. Getting it through Congress was very difficult, very controversial — but the results were spectacular. It was the fulfillment of that idea that Kennedy had that a rising tide lifts all boats.

I think the thing for Dillon was always that, yes, you could introduce tax cuts. And that was something that he wrangled with various Keynesian economists, like Paul Samuelson, for example, and Walter Heller about, but he also thought that you had to reform the tax system. That was even more controversial, trying to introduce these tax reforms.

It’s interesting that the Reagan administration, in the 1980s, very much took the ideas that Dillon had had in the 1960s. The kind of reforms that James Baker introduced were very much ideas that Dillon had been promoting right back in the 1960s.

I think in terms of the kind of current politics, you’re right. There does seem to be a sharp contrast, for example, in the policies of the Biden administration — Bidenomics, I suppose. It’s very much the kind of industrial strategy or industrial policy that Dillon was moving away from. And as you said, the modern Republican Party is very different in terms of its outlook, too.

GE – How did Dillon navigate the relationship between the Treasury Department and the Federal Reserve during his time as Secretary? And what kind of precedent did that set for future Treasury officials?

RA – It’s actually one of the major innovations that Dillon had.

He was very aware that in the past, there had been huge political rows between the Treasury, the Council of Economic Advisers, and the Federal Reserve. He was determined, if not to eliminate those debates, to make sure that those debates took place within a close and structured environment.

He actually formed something that he called slightly tongue in cheek, the Troika, which was the Treasury Secretary, the chairman of the Federal Reserve, and the chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers. And they would meet together, very often with the president, so that these issues could be thrashed out in a way that was clear and transparent.

So, I think that that idea of working together or moving together in lockstep was something that he particularly valued. Even Heller, with whom Dillon often had strong differences of opinion, said in all the oral history interviews that he did that this worked. That he always found Dillon to be very courteous and very cooperative, even when they disagreed on major issues of policy.

GE – Dillon was at the helm of the Treasury during some of the biggest crises of the second half of the 20th century. Notably, the Cuban Missile Crisis and the Kennedy assassination. How did he manage those situations? And did his actions provide a template for future Treasury leaders?

RA – Those two crises were absolute turning points for Dillon. He acquitted himself incredibly well. He was a member of the National Security Council during the Cuban Missile Crisis, so he was right at the heart of decision-making.

The crucial thing there was not just about averting nuclear war. It was also about making sure that there wasn’t a major meltdown in the markets, too. He had put plans in place for exactly this kind of eventuality. It was something that gave him a real sense of pride and achievement — that it worked during the Cuban Missile Crisis.

There weren’t major withdrawals, for example, or a loss of value of the dollar, and major withdrawals from gold reserves, and so on. He had put deals in place with banks around the world to avert this kind of crisis.

Following the assassination of the president, he was dealing with the loss of a personal friend. Of all the cabinet members, probably Dillon was the only one that John F. Kennedy counted as a friend. The only one that he dined with, socially, with their wives in the White House, and so on. So he’s going through all of that but also making sure, again, that there isn’t a meltdown in the global economy.

It’s a good example of what you were talking about before because he had all of these plans in place. He had all of these agreements with various central banks around the world. He was also able to use those connections. He was a close friend with the Rockefellers. They’d been to the same school. So immediately, he was able to get Nelson Rockefeller, the governor of New York, to shut the stock exchange. To make sure that there was time for the global markets to calm down.

GE – Before we end, I’d like to ask you if, during the process of researching and writing this book, you got some sense of the man. Who was he?

RA – I found him a genuinely fascinating character to work on. Because, you know, on one level, it’s very easy to see him as a child of privilege. As a very entitled person that comes into politics as ambassador to Paris, in the way that very many people do get those kinds of ambassadorships.

Because his family had been a major donor to the Eisenhower campaign. Because he was friends with John Foster Dulles, the Secretary of State, or at least his father was friends with John Foster Dulles.

So, on the one hand, there is a sense of entitlement. But then you literally see this character developing in front of your eyes because he’s actually a very successful ambassador in Paris. Then, when he comes back to the State Department and then in the Treasury, he’s a highly effective, highly accomplished, and highly popular member of both administrations.

I think that it does speak to a different kind of age as well. This is before all the civil unrest of the 1960s when, frankly, I think it’s easier to be a patrician figure like Dillon, who nevertheless has a sense of duty. A sense of the national interest. A sense of wanting to improve the lives of those who are less well-off than himself.

In that sense, he’s a typical conservative figure of the old school. Somebody who wants change to come but sees it evolving, but also sees that he has an obligation as somebody of great privilege to help those who are not privileged in society.

It’s a fascinating life. He’s a fascinating character and certainly somebody who I think has been underappreciated and overlooked when it comes to the politics of this era.

GE – Professor Aldous, I want to thank you again for taking the time to speak with us. It’s been a real pleasure.

RA – Thank you so much. I’ve really enjoyed it.