How Bankers Helped Save Russia’s Jews

Andrew Barber — March 14, 2024

During the late 19th century, the rise of new technologies like railroads, telegraphs, and ever-larger steam-powered ships fueled an explosion in commerce. This increase in global trade created massive opportunities for bankers who had the vision to recognize a growing need for cross-border capital.

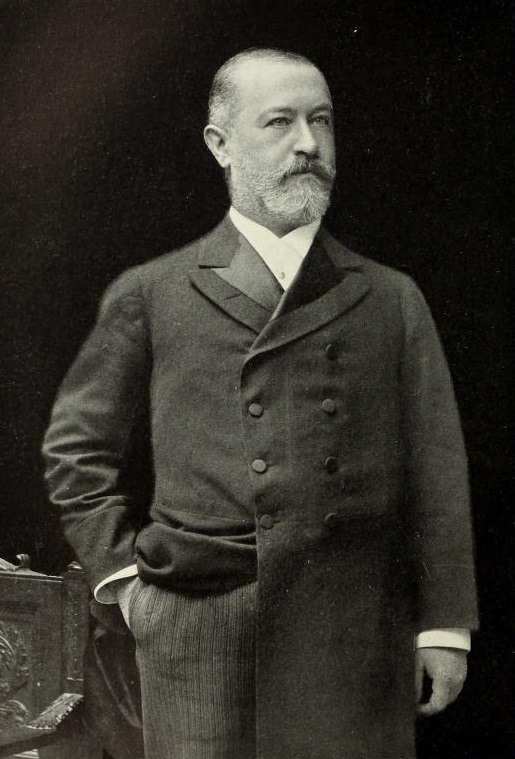

Among the most prominent of this new breed of international financiers was Jacob Schiff.

The head of the great banking house of Kuhn, Loeb, Schiff was a rival of J.P. Morgan and business partner of E.H. Harriman. His innovative work helping governments raise money in the US and European bond markets placed him among the giants of Wall Street history.

This international demand drove rapid expansion in the US economy, attracting a wave of immigrants from Europe. Among those millions sailing to America were Jews fleeing oppression in central and Eastern Europe.

Our guest today is Steven Ujifusa, author of the excellent new book The Last Ships from Hamburg, which explores the role Schiff and other business leaders played in shaping the Jewish component of this great migration.

Perhaps more than any other man of his time, Schiff helped shape both the perception of the Jewish community in America and its political voice. He also championed the cause of aiding Jewish refugees – particularly those fleeing oppression in czarist Russia.

In a compelling narrative rich in detail, Ujifusa tells Schiff’s story, as well as the stories of other businessmen involved in the race to save the Jews of Eastern Europe.

Listen to our interview with Steven Ujifusa:

Andrew Barber

Steven, your book starts in the later part of the 19th century, and it relates to migration from Eastern and Northern Europe to the US. Could you walk us through the geopolitical situation in that region then and how the US fit into it from an economic and foreign policy standpoint?

Steven Ujifusa

In 1881, it’s really about immigration. Mass immigration of Jewish people from the Russian Empire to America literally began with a bang, and the fascination is that’s when Czar Alexander II, who was one of the progressive czars who had liberated the serfs in the 1860s, was assassinated in St. Petersburg by an anarchist group. And his son, Alexander III, took over, and he declared that ‘All of my father’s reforms have led to instability and chaos.’ And he conveniently blamed Russia’s four million Jews for fomenting this threat to the Russian royal family into Russian culture.

So, he, along with a group of advisers, decided that Russia needs to purge itself of these – what he called – foreign or dangerous elements in society. The Jews had been the scapegoat in Russian history for centuries before. And he began a program of pogroms of persecution of military conscription of young boys that basically kept them in the army for 25 years and basically got rid of their Jewish culture by taking them away from their families. One of his advisors who would go on to tutor his son, the future Nicholas II, would say, ‘The ideal situation would be that one-third of Russia’s Jews emigrate. One-third convert. And one-third simply disappear.’

So, this was state-sponsored antisemitism. And this was happening at a time when other European countries, such as France, Germany, Austria-Hungary, were liberating their own Jews and giving them full civil rights and citizenship. So, Russia was going against the grain of other European countries. This left Russia’s Jews mostly residing in the so-called Pale of Settlements, where they were mostly confined to live. This is modern-day Ukraine and Belarus and other countries in that area. These are territories or states that were under the control of the Russian Empire.

This gave them a very stark choice. They can either stay and wait it out and be fearful of pogroms that were sanctioned by the Russian Orthodox Church. They could lie in wait and be afraid of Cossacks on horseback that would come and kill them, take their property, rape and pillage, or they can leave everything they knew behind and make out for a new destination. A lot of other European countries, such as Germany, were largely closed to them, but America at the time – the 1880s and 1890s – had a relatively open immigration policy.

So, this was the promise. This was the hope for a better life. And ultimately, over 2 million Jews left Russia for America. And this was a very difficult voyage. It was not only just saying goodbye to everything you know — even if the old village was wretched, as one historian said, ‘A thoroughly known place’ – to drop everything you know, say goodbye to everyone you know, get on a train and find your way to the border with Germany. There was no major Russian seaport from St. Petersburg at the time. And so the best hope for them was to get through Germany and make it to the ports of northern Europe and to Bremen and especially Hamburg. So, this involves illegal border crossings to get to these ports. And it required these families to sell everything they owned – most Jews in the Russian Empire were poor – to make this dangerous voyage. A number of steamship lines, including the Hamburg America Line which is owned by a German named Albert Ballin. Sorry. Not owned, but managed. He devised a system that allowed these migrants to cross the border. His company and a few others took control of these border crossings, put them on trains, and sent them to these ports where they board ships to America.

Andrew Barber

What was the Jewish population of the US like at that point in terms of national background? You’ve mentioned Germany. And certainly, there were a lot of Jewish families of German descent in New York and in some of the major East Coast cities. What was the general reception on the part of the US government and society broadly? Were there organizations to assist them with transition and assimilation?

Steven Ujifusa

Well, most of America’s Jews before the 1880s were of German descent. There are a few of Sephardic descent that say there were Jews in America since the 17th century. The first synagogue was set up in New York, I believe, in the 1650s. But the German Jews that came over to this country mainly came over after the failed revolutions of 1848. A lot of them would come over very poor, and they were peddlers and sold dry goods. And by the 1880s, a lot of them had become quite wealthy. They had become bankers. They had become department store owners like the Straus family. And then you had Jacob Schiff, who had started off at the firm of Kuhn, Loeb when it was in Cincinnati. It was a dry goods business but then had moved into investment banking, underwriting the governance of railroads.

So, Jacob Schiff was someone who had made a fortune as an investment banker – he was second only to J.P. Morgan as a financier. [Schiff] was a very shrewd, very skilled man but a very dedicated philanthropist. And he felt the promised land of the Jews was the United States. This was the new Israel, and the Jews could come from Russia to America, and he would be the one to set up charities and acculturate these Russian Jews to American life.

Now, a lot of his other fellow German Jews really looked down on these Yiddish speakers. They spoke basically a form of Low German. They were a very different culture. Much poorer. And a lot of Germans felt this made them look bad. And there was a significant spike in antisemitism starting in the 1880s, 1890s among the Protestant upper class when before Jews had been, if not entirely welcome…at least accepted. [Especially] the most successful ones, like Emma Lazarus’ family. [She] is a woman who wrote ‘The New Colossus,’ which is on the base of the Statue of Liberty.

But there was a tension between these older stock Jews of German origin and the Russian and Eastern European Jews, and Jacob Schiff took it upon himself to spend – I think he gave away about half of his fortune – to develop things such as the Henry Street Settlement, which provided classes and education, vocational training for Jews. He was a big patron of the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society, which gave out small loans to business owners who were starting all sorts of small enterprises.

In fact, a loan from that organization helped get my wife’s great-grandfather’s family off the ground with a loan of 50 bucks. My great-grandfather-in-law became a successful leather merchant. These are the sorts of small microloans that would help. So, Schiff was the sort of person who said, ‘I want to acculturate these Jewish arrivals.’

Now, that met with some resistance from the Russian Jews who felt, ‘Who are these haughty German Jews to tell us how we should be American?’ A lot of them were also considerably to the left in terms of politics. A lot of secular Jews in America had become Marxists, socialists, and Schiff, as a capitalist, found that rather than dangerous. So, there’s this tension between the Russian Jews and the German Jews, between the Uptown Jews and the Lower East Side Jews. But they were bound up with each other.

Andrew Barber

Schiff was also very active in secular charities, correct? He was very active in charities that were specific to New York City and with immigration. He was also a man whose name is still on a lot of buildings in New York City. As far as his approach to business, he had been at the helm of Kuhn, Loeb when it became one of the most powerful banking firms in the US. Under his leadership, it became the primary competitor of J.P. Morgan in issuing bonds for railroads and railroad M&A. And, of course, his work with Harriman and his own corporate empire-building. With all of this influence, how did he build relationships with elected officials to advance his goals for immigration? How did the relationship with his rivals on Wall Street develop?

Steven Ujifusa

That’s a fascinating story because Schiff was a loyal member of the Republican Party. And he also was a very great supporter of Theodore Roosevelt. And Theodore Roosevelt, who was born and bred in New York City despite his patrician background, unlike many of his peers, he himself was a friend of the immigrant as long as they assimilated to American life. And so, Schiff and Roosevelt developed a close friendship. Schiff also donated a lot of money to Harvard University. He was very close with President Charles William Eliot, and they spent summers together in Mount Desert Island, Maine. I think, both through political involvement and through involvement in places like Harvard, what Schiff’s goal was for American Jews – Germans, but also eventually Russians – to rise into the American establishment.

Schiff had a very strange ability to be an extremely religious Jew, very much based his entire identity on his religion. He only served kosher food in his house. Sabbath services were strictly observed at his house on the Upper East Side. But he also, thanks to his connection with Harriman and the Rockefellers, was able to have an entrée into gentile society. Not everyone, though, appreciated that. There were people who did not like his presence, but he lobbied very hard to keep America’s immigration doors open.

He also worked with Jewish politicians, who were starting to be elected to office, to keep this open immigration policy. Unfortunately, some of Theodore Roosevelt’s friends from Harvard were founders of an organization known as the Immigration Restriction League. Founded in the 1890s by his dear friend Henry Cabot Lodge, who did not feel that Jews or Italians or Eastern Europeans or Southern Europeans could assimilate into American life. And they felt that this was going to degrade the genetic stock of the country.

This was the beginning of eugenics. As one member of the Immigration Restriction League said, ‘These are beaten men from beaten races.’ Now, this was an elite antisemitism that started off in places like Harvard, MIT, Columbia University, and in high society, but then eventually, by the 1910s, had filtered into popular culture. So, this is what Schiff found himself fighting against. He also worked closely with an organization called the Liberal Immigration League, which was the pro-immigration counterpart. He also was good friends with the Straus family. Oscar Straus was the first Jewish cabinet member who was Secretary of Labor under Roosevelt. Oscar Straus helped oversee many crucial reforms in the acceptance of immigrants at places like Ellis Island, but the Immigration Restriction League complained that because Straus was Jewish, he was letting too many immigrants through. People who were unfit for America, in their words.

Andrew Barber

Of course, Henry Cabot Lodge was an isolationist in terms of his approach to the role of the US abroad. In addition to his views on immigration, he ultimately ended up being instrumental in defeating the US involvement in the League of Nations. He was very much somebody who, in addition to rejecting international cooperation, favored US expansion. So, as Schiff was navigating the Republican Party while managing his business and his charitable endeavors, he faced a stark contrast between politics and commerce. A core pillar of your book is discussing the rivalry with J.P. Morgan, his role, and, to a lesser extent, some of the other financial houses in New York that were not historically Jewish. Could you walk us through how this rivalry grew into a catalyst for action?

Steven Ujifusa

Yes, it was interesting because you had a confluence of finance and diplomacy going on. You had two large pools of money that wanted to invest in American enterprises, specifically railroads, but other businesses. You had British capital that was earned for the British Empire. And you had Barings Bank in London, which was the premier British bank. J.P. Morgan and company had long had a relationship with the Barings brothers and these British banks, as did some of the other ‘gentile banks’ in investment banks. And they served as conduits for this British capital that was coming and also French because J.P. Morgan also had an office in Paris. So, you had the British and French capital.

Schiff was a conduit for Central European capital investment into railroads and American enterprises. You had Kuhn, Loeb & Co. You also have the Rothschilds. And this was German and Austrian money that was being funneled in.

One thing that’s really changed that we don’t think about is that Jews and Jewish bankers in the late 19th or 20th century were specifically associated with Germany. There was a very strong symbiosis at the time between Germany and Jews. You have this whole network of family connections between Kuhn and many German banks, most notably M.M. Warburg & Co. in Hamburg. The partners of Kuhn, Loeb, in many cases, married people in the Warburg family in Hamburg. So, a lot of it wasn’t just business. It was family. Very tightly knit.

And there was also the connection with the Rothschilds. And the Rothschilds had branches in major European cities and also had a branch in New York City. In fact, a gentleman by the name of [Aaron] Schönberg – who later was known as August Belmont. He was originally a Jew from, I believe, either Frankfurt or Cologne, who had come over as a representative for the Rothschilds. Of course, everyone would get to know him in post-Civil War New York. He became very wealthy on his own, created his own company, and then converted to Christianity and formed his own bank called August Belmont & Co. But if you had connections with the Barings or the Rothschilds, you were very popular in New York City. And hence, Morgan had its relationship with Britain and France; Kuhn, Loeb had its relationship with Germany and Central Europe.

Andrew Barber

In your book, you detail the vision of the bankers in New York who are part of this demographic, this cultural shift in identity both in New York and in Europe, and, to a much greater degree, New York. The obvious counterpoint to this is the Russian Empire. Probably the most famous bond issue Schiff worked on was the Japanese issue in the aftermath of the Russo-Japanese War, which I believe had him be the first American to be directly recognized by the Emperor of Japan in a non-diplomatic context. So, through the course of your narrative, the Russians appear to be alienating themselves from the great financial houses. An obvious question is whether czarist Russia was undermining its future with a decision that began a downward spiral for the czarist regime.

Steven Ujifusa

Yes, that’s a very good way of seeing it. Russia was doing whatever it could to preserve an ancient autocracy, even if it meant falling on its sword. When Czar Nicholas II took power after his father’s death in the mid-1890s, he was not a particularly bright or imaginative person. He believed that he was ordained by God to be an autocrat, and that’s how things were. And he felt, ‘We are sort of the last stand of divine right monarchy.’ Unlike what’s happened in Britain or France, which, God forbid, had become a republic, or even Germany, which, although the Kaiser had a fair amount of power, he still had a Reichstag. The idea of having any representative bodies to Nicholas II was utterly repellent. And the Russo-Japanese War was, in many ways, Nicklaus II had this idea that these people are racially inferior to us. We could easily conquer them or beat them. Well, this proved wrong.

And Jacob Schiff saw an opportunity to basically stick it to the eye of the czar because he considered Russia to be the great Satan of the Jewish people. And he actively sought to support the Japanese government’s war effort against Russia. He floated very successful bond issues. In fact, one of these bond issues is so oversubscribed that he sent it to his son-in-law’s brother over in Hamburg to M.M. Warburg & Co., and it was successfully oversubscribed in Germany. So Schiff’s effort helped defeat Russia in this war, and it was humiliating to the Russians.

Schiff, he was decorated by the Japanese emperor. He was given the royal treatment. He hosted a Japanese princess in his house in New York. And he felt that his duty was to make life difficult for Russia, as that was part of his mission. In fact, it did kind of lead to his humiliation many years later during World War I, where he refused to…

Before America entered World War I, there was a fair amount of German sympathizing among the population, and Jacob Schiff in 1914 said that, ‘I could not turn my back on the fatherland. It’s been overall good to me. And why should I support an alliance between Great Britain, France, and Russia?’ He had no problem with Great Britain…but when asked to float war bonds, he said, ‘I will do it if Russia is not in on the deal.’ So, he miscalculated in 1914-15 the amount of sympathy that would ultimately head over towards Britain, France, and Russia. Although, Russia in 1917 was taken out of the war by the revolution.

Andrew Barber

Schiff was not only very involved in philanthropic activities focused on aiding Jewish refugees from Eastern Europe but was also politically involved in lobbying for a more active US role in global policy. And, certainly, J.P. Morgan was extremely involved in shaping US policy. Both men maintained close relationships with leaders in both the Democratic and the Republican parties. Today, of course, we are used to financiers lobbying on Capitol Hill for policies that will be good for their businesses. Did the financiers in the 19th century, particularly these two men, have a different approach to balancing their business interests with social responsibility?

Steven Ujifusa

Back in the late 19th century, the Gilded Age, there was no welfare state whatsoever. There [were] no government programs to assist those in need. And J.P. Morgan wasn’t particularly philanthropic, except when it came to humanitarian aid. His main interest was art and culture, but not helping the oppressed. Jacob Schiff, on the other hand, felt a very strong belief in the old Jewish philanthropic principle of tzedakah. Making the world whole. Of tithing. Of giving a significant portion of his income to help his people. And I think Jacob Schiff stepped in in many ways to where the welfare state did not exist.

You did have among Jewish immigrants in the Lower East Side the small organization called Landsmanshaftn, which is Yiddish for basically a hometown association. People that came from the same town or region would welcome new arrivals. Pool some money to help set them up. But I think Schiff felt that given his wealth and power and prominence, he was the one to take the lead, and he was definitely known as an autocrat.

He was often very disagreeable when he was contradicted, but he had a mission, and he successfully achieved it. And when he died in 1920, his funeral took place at Temple Emanu-El. And there was no eulogy given at his request. As one famous politician said at the time, ‘He doesn’t need a eulogy. He just needs who he is.’ And the great and the rich and the good were inside the synagogue, Jew and Gentile alike celebrating Jacob Schiff’s life. But outside were thousands and thousands of poor Jews from the Lower East Side and Brownsville Brooklyn who had come all the way uptown to pay their respects to this man who had helped make their lives better in America. So, he really took this to heart.

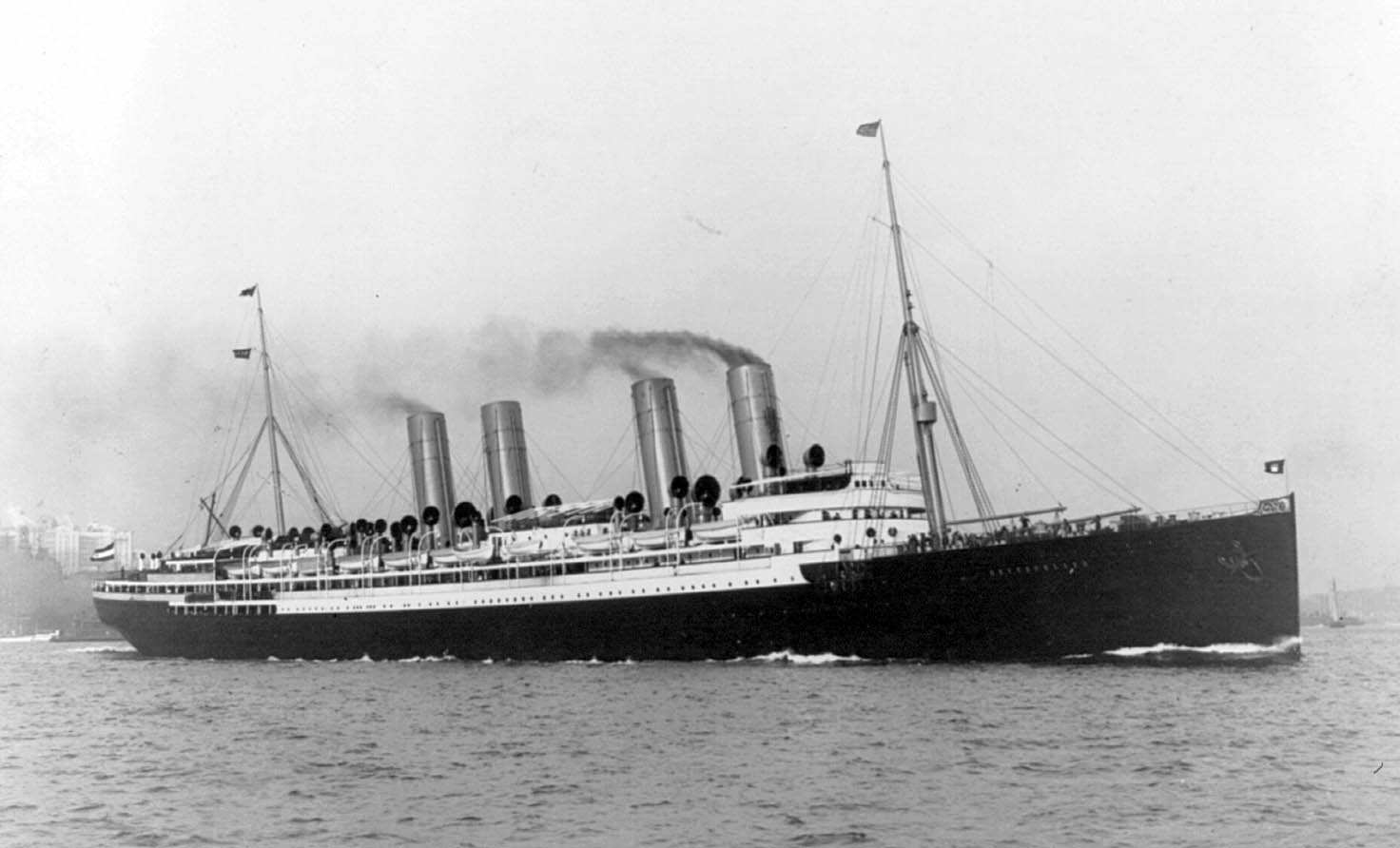

I think also when it came to business, J.P. Morgan really didn’t care that much about humanitarian aid. He cared about bringing over cheap labor to the United States to help man the factories and the mines and the railroads. And the reason why he invested in the International Mercantile Marine, which was an attempt to corner the steamship trade between the Old World and the New, was to make money off the immigrant trade. It was a very lucrative business. You would have big liners in the 1900s. You’d have 600 in first class, 500 in second, and 2,000 in steerage at 25 bucks a head. A great business model. You use absolutely minimum resources, pack as many people as you can into the hulls of these grand liners, and Morgan wanted to make a buck off this.

Unfortunately, he was prevented from having a monopoly because of the Hamburg America Line, which was controlled by Albert Ballin, who was close to Jacob Schiff. In fact, Jacob Schiff and Kuhn, Loeb and its counterpart in Germany, M.M. Warburg & Co., helped finance the growth of Hamburg America Line. J.P. Morgan couldn’t get his hands on that company due to Albert Ballin’s intelligence and the direct intervention of the Kaiser. So, that cost him dearly and made his steamship enterprise one of his very few failures.

Andrew Barber

Jacob Schiff is obviously one of the key personalities in your book. You present him as a man of his time. With a worldview that was not ‘progressive’ in the sense we think of today. Ultimately, when we discuss the issues he was passionate about, how do you think his vision differed from the consensus views of his time? And how do they differ from consensus thinking today?

Steven Ujifusa

Well, I think that Jacob Schiff was not a supporter of Zionism because he felt that, ‘Why do you need to have a homeland for the Jewish people in Palestine when you have the United States? You have the Constitution. You have the founders.’ And he believed the Jews – if they came to this country – they could be like him. They could come here and integrate into American life while still retaining their religion. They basically subscribe to the founding vision as laid down in the 18th century, which was a huge improvement over autocracy in Russia. He felt this is where the Jews can flourish. He even tried to found a settlement of Jews in Galveston, Texas. His idea was the Jews need to be scattered more uniformly throughout the country versus being confined to cities such as New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Boston. He believed that there would be less antisemitism if Jews were not concentrated in big East Coast cities.

But yeah, in terms of being a person of his time, he was very rigid. He was feared as a kind of a religious zealot and was not the warmest person. But he definitely felt a deep need to turn immigrants into people like himself. He believed in the American dream.

I mean, he definitely struggled with it. He didn’t say it out loud. But on one hand, he socialized with members of the gentile elite and worked in gentile circles, but he didn’t really socialize that much. He devoted himself to his family and to his charities. He was excluded from many social organizations, but I don’t think that bothered him that much. And yeah, I think for him, family was the most important thing. He was very devoted to his family, but he did specify in his will that children or grandchildren who married outside the faith would be disinherited. He wanted to preserve Judaism within the family, which was very much ‘a man of his time.’ He did not want his family to fully assimilate, as in like not be practicing Judaism.

Andrew Barber

I’m assuming it took you several years to research and write this book.

Steven Ujifusa

Yes, it was. Pretty much four years from start to finish.

Andrew Barber

Over the course of writing this book, the world has changed dramatically. Now, we find ourselves experiencing geopolitical strife with conflicts in the Middle East and Eastern Europe and, of course, rising tensions in Asia. Much of this is being driven by ethnic and cultural animosity, by conflict between autocratic governments and democratic governments. Additionally, both Europe and the US are wrestling with a wave of immigration and a resulting backlash from populist politicians. So, in a way, our own time echoes tensions of the late 19th and early 20th centuries before the final crescendo in 1914.

What do you think Jacob Schiff would have thought about the problems we are facing now? Are there lessons we can take from his life’s work?

Steven Ujifusa

I think there are many, many lessons to look at in the lead-up to World War I. I think that everyone talks about World War II and the 1930s and Germany or whatnot. Leading up to World War I, there was a similar feeling of confidence that everything was settled. It was the end of history. You had the British Empire, which was ‘the great empire that lasts forever, the sun will never set.’ There’s a sense of certainty among people. And how it all eventually collapsed.… All the leading families of Europe – the royal families – are all interrelated. So, how could they possibly go to war?

Well, it turns out they are just as dysfunctional, if not more dysfunctional than typical families. And I think that Jacob Schiff, he died kind of a shaken man in 1920. I think that, like a lot of people who came of age – I think there’s a lot of similarities in the 1890s and early 1900s and the late 1990s and early 2000s –there was a surge of confidence and feeling of safety. This feeling of like, ‘We’ve reached the end of history.’ And a lot of people staked their sense of calm and identity and confidence in it. And then, when it all fell apart, I think it caused people like Jacob Schiff to really, really evaluate what was going on. He had placed his loyalty to the United States. He also felt very strongly pulled by Germany through culture and through business ties.

And I think he felt the breaking point for him was the sinking of the Lusitania on May 7, 1915, which was an attack by a U-boat on a British luxury liner. Yes, she was carrying 2,000 civilians, but she was also carrying many, many cases of small arms ammunition, and that was seen by the Germans as a legitimate war target. When that ship was sunk and killed 1,200 people, public opinion turned against Germany. And he did his best to try to rationalize it, and that cost him dearly. So, I think he really felt like someone who had placed his faith in the American experiment and placed his faith in the future of Germany, too.

He also began to see by 1914-15 that there were forces in the United States, first as an elite circle but then growing popular circles of people who did not want Jews or Italians or other Southern Europeans in this country. There’s a rise of eugenics at this time. And Schiff was seen as someone who was bringing in these people that were going to ruin the country, in their words. And I think that was really jarring for him. I think he had to pivot. He was old at the time. He was in his 70s when World War I began. He had to pivot to being a full-on American patriot in order to save his own sense of self and his business. And I think that’s when he began to really go even deeper into his faith.

He also began considering maybe the idea of a Jewish homeland might make sense. That during the devastation going on in Europe, there were many, many Jews in the Russian Empire who were caught on the Eastern Front and killed by the Russian army and persecuted. So that really scared him. Seeing how Jews were being treated during World War I.

So, I think he was shaken. He was deeply shaken. But he was too old when he died in 1920 to fully pivot into a new worldview. Then in the 1920s, America did pivot into nativism. Congress passed a series of acts which basically barred Jews from the former Soviet Union and the new country of Poland from coming to the country, which basically doomed them when the Nazis invaded the Soviet Union and took over Germany. So, I think he would have been horrified to see the full extent of how this sort of unfolded.

Andrew Barber

He really bought into the promise of the late 19th century. That global development, interconnectedness that was both economic and cultural, could help bring finally peace to replace the endless conflict that the Western world had known prior.

Steven Ujifusa

Yes, I think that’s what it came down to. I wouldn’t say he died disillusioned, but he died shaken. And a similar fate befell his business associate, Albert Ballin, who was head of the Hamburg America Line. When the war started in 1914, his company had grown into the biggest shipping company in the world and carried more immigrants from the Russian Empire than any other company. He had been heavily financed by M.M. Warburg in Germany, and just before the war started, Kuhn, Loeb was about to float a public offering of stock of the Hamburg America Line on the New York Stock Exchange. Well, that was ended.

Albert Ballin was not a religious Jew but culturally Jewish. He married a gentile but had never converted. He always found himself walking a tightrope between his Jewish identity and the power circles of Wilhelmine Germany. The Kaiser was friendly with him, although he didn’t say nice things about Jews in private. And when the war started, now that Ballin had worked very hard behind the scenes using his business clout to stop a war between England and Germany, he exclaimed, ‘My life’s work is ruined,’ because that cut off all immigration and ruined his business. And I think he died in 1918, similarly broken and sad about what happened in Germany.

And I don’t know about Schiff, but he sort of wondered, ‘Okay, what’s going to happen in Germany next was not going to be nice.’ He was always afraid that there were antisemites everywhere, no matter how high he rose.